The extent of financial innovation seen across the financial markets is never ending. Despite the Covid-19 pandemic, 2020 was the busiest year on record for Initial Public Offerings (IPO) for both traditional listing and SPACs, and the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) ranks as the number stock exchange for IPO Proceeds.

It (NYSE) raised $81.8 billion in IPO proceeds with 163 transactions (listings), hosting 6 out of the 7 largest Tech IPOs of 2020, and 63% of SPAC, proceeds of which (SPAC) included the 6 largest SPAC IPOs of the year.

SPAC, what is SPAC and SPAC IPO? This is the question this article seeks to answer. $4 Billion was raised in the largest SPAC IPO of the year 2020 with Pershing Square Tontine Holdings.

Investopedia defines SPAC as “Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) is a company with no commercial operations that is formed strictly to raise capital through an Initial Public Offering (IPO) for the purpose of acquiring an existing company.

- Read also; NSE weekly report: N1.042 Trillion Christmas gift for Investors

- Domestic Economy: National Assembly Approves 2021 Budget, Raised Up Figure by NGN505.6bn

In other words, SPAC is a company created solely to merge or acquire another business and take it public. Investors essentially write blank checks to SPACS, which can take up to two years to target and buy another firm.

After the IPO, the stock of these SPAC companies that has no operations, no assets, and nothing else other than a war chest of cash is publicly traded on stock exchanges. Prior to any merger or acquisitions, SPACs have just one stated business plan: to eventually buy another company.

A SPAC is generally formed by a group of investors, called sponsors, with a strong background in a particular industry or business sector. They raise funds from other investors, and use the money to acquire an existing, privately held company — and then take the newly acquired company public in an IPO.

When they launch the SPAC, the sponsors generally either don’t have a specific target in mind, or they’re not ready to name it in order to avoid the extensive paperwork and disclosures required by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

The early-bird underwriters and institutional investors, and the individual investors who generally come in later, typically have no idea exactly how the sponsors will spend the money. So early investors are basically relying on the sponsors’ reputation in the hope of snagging a good investment.

But they’ve got to be prepared to wait. Even after a SPAC goes public, it can take up to two years to pick and announce the target company it wants to acquire, or technically speaking, merge with (the corporate charter specifies the exact time frame, per SEC regulations). If it doesn’t, the SPAC is liquidated, and funds it’s raised are supposed to be returned to investors.

The uncertainties surrounding the next action SPACs will take normally keeps their prices low. The assumption is that when, and if, they acquire a company and take it public, the share prices will soar. At this point, investors can cash out, or hold on for longer-term gains.

As with all things, giving the sponsors of SPAC a blank check brews a perfect situation for abuse. In the 1980s, a lot of fraud surrounded similar ventures, know then as blank check companies.

Many of the blank check companies were purely shell companies, offering thinly traded penny stocks. Often these firms either absconded with investors’ cash or engaged in overvalued insider deals that left many investors with a bagful of nothing.

A lot of regulation has come in since the 1980s, with the Security and Exchange Commissions tightening regulations and procedure for these ventures, and the name was changed to SPAC.

Now, for example, a SPAC generally has to place the investor money in a trust or escrow account to keep it secure until the target company is publicly announced. At that point, if investors don’t like the looks of the deal, they should be able to recover their funds. SPACs also have to register with the SEC, even if they’re relatively small.

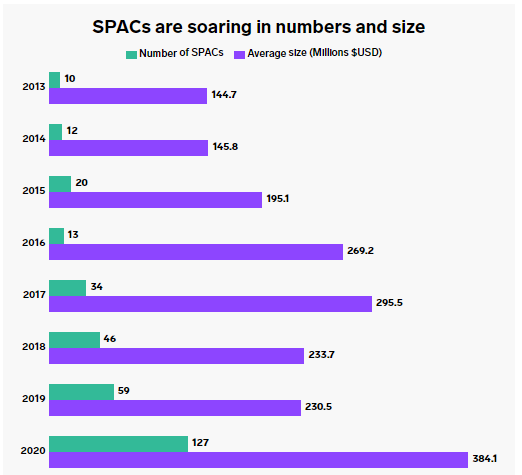

SPACs has been soaring in numbers and size, with 2020 being the biggest year for it, in both the number of SPACs listed and the average size.

Source: Business Insider

Just like every investment, SPACs have advantages and disadvantages;

Advantages of SPAC

- They’re cheap. Many SPACs are priced at $10 a share, well within reach of retail investors. And they stay low for a while. “SPAC IPOs on average don’t jump on the first day of trading,” notes Jay R. Ritter, the Joseph B. Cordell Eminent Scholar Chair at the University of Florida’s Warrington College of Business, who researches IPOs. “The average increase this year on the first day of trading has been 1.7%, so buying in the market might mean paying $10.17 or so.”

- They invest in hot areas. The new breed of SPACs focuses on sexy sectors in the tech or consumer fields. Promising startups like Opendoor, Clover Health, and electric automaker Nikola are among the firms that have gone public via SPACs.

- They’re open to individual investors. Even though institutional investors usually go to the front of the line for SPAC offerings, the high number of shares sold makes it easier for smaller investors to get a piece of the action.

Disadvantages of SPACs

- Blind investment. SPAC investors usually don’t know how their money will be used — what the SPAC’s target company is (often the sponsors don’t know either). So the deal’s impossible to evaluate.

- Lag time. There can be a long lag between the time investors pump money into a SPAC and when it actually buys up a company and starts operations. Your money may sit for up to two years in an escrow account. If no acquisition happens, your funds are returned, but idling capital for that long may be painful.

- Mixed track record. In a July 2020 report, Goldman Sachs analyzed the performance of 56 SPACs — primarily in the technology, industrials, energy, and financial segments — that “merged” with their target companies beginning in January 2018. “During the one-month and three-month periods following the acquisition announcement, the average SPAC outperformed the S&P 500 by 1 percentage point (pp) and 11 pp, respectively, and beat the Russell 2000 by 6 pp and 15 pp, respectively,” the report notes. “However, the average SPAC underperformed both indexes during the 3, 6, and 12-months after the merger completion.”

How to invest in SPACS

Getting into a SPAC is not as simple as buying regular equities: Hedge funds, mutual funds, and other deep-pocketed institutional investors typically find out about a new SPAC first. “It helps if a would-be investor has an existing relationship with a SPAC sponsor,” says Tyler Gellasch.

But if Michael Jordan isn’t among your contacts, there are other ways to break into the world of SPACs:

- Your friendly stockbroker or wealth manager. Ask them to keep an eye out for offerings

- The websites of IPO-oriented investment banks. One SPAC specialist, Early Bird Capital, lists companies that are actively seeking targets.

- The NASDAQ website also lists upcoming IPOs, including SPACs, which can be identified by a ticker symbol that generally ends with a “U.”

- Industry associations like SPAC Research sometimes highlight S-1 filings, which give formal notice of a SPAC’s intention to go public.

Business Insider summaries the financial takeaway very well in its publications about, from which most of this write-up is based;

A SPAC is definitely not “a ‘widows and orphans’ investment,” according to Gellasch. “For one thing, you may be tying up your money for a year or more without knowing what the ultimate investment will be. The sponsor and institutional investors may know — at least generally — what they’re looking to do with the funds, but the small investor will likely be in the dark.”

“Until a deal is announced, the investor is just hoping that a good merger will happen,” Ritter adds. And of course, there are no guarantees as to returns after it does. SPACs are speculative animals. They tend to acquire growth companies — start-ups and fledgling firms — which, by their nature, are higher-risk than, say, established blue-chip companies.

Still, SPACs offer smaller investors a way to get into the IPO game — if not up in front with the big players, at least not too far behind them.

Of course, some SPACs do better than that. For example, Virgin Galactic Holdings (SPCE) — a particularly high-profile offering — has appreciated 146% in the year since it went public via a SPAC in October 2019.

By; Nnamdi M.